Debugging tactics

Overview

Teaching: 60 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

What is debugging?

How can I debug a problem?

What tools are available to help me with debugging?

Objectives

Understand python traceback messages

Learn to use the logging module

Learn to use a debugging tool

Getting things wrong

Much of academic software development involves writing code that is broken, adjusting it until it works, and then moving on. This similar to the process of learning anything - getting it wrong until you get it right. The process of debugging is typically thought of as finding all the errors and fixing them. Largely this is correct, however there are also strategies that you can use to reduce the number of errors along your path to a final solution. These techniques are like good study habits - they speed up your learning process.

The first thing to learn when debugging code is that all code has bugs. So the first step in debugging is to embrace this and accept it, and not feel bad about having bugs in your code. Shame doesn’t help anyone. Even professional software developers don’t write bug-free code, they just have strategies and processes in place that will:

- reduce the number of bugs introduced

- make bugs easier to identify

- reduce the severity/impact of existing bugs

We have already learned some strategies that will help write better code, all of which will result in fewer bugs:

- Clarity of efficiency

- Naming is important

- Don’t repeat yourself

- Don’t repeat others

- Document

- Test

- Version control

In this lesson we’ll explore ways to identify and squash the inevitable bugs that will occur in our python code.

Understanding the python traceback

The easiest kind of bugs to identify are those that crash your program, because they will generate a traceback of the python call stack that shows you where an error occurred. An example is given below:

python3 mymodule/sky_sim.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "mymodule/sky_sim.py", line 119, in <module>

ras, decs = make_positions(ra, dec)

File "mymodule/sky_sim.py", line 87, in make_positions

ras, decs = crop_to_circle(ras, decs)

TypeError: crop_to_circle() missing 3 required positional arguments: 'ref_ra', 'ref_dec', and 'radius'

The first thing to note about tracebacks is that they are traceBACKs meaning that you should read them backwards.

The last line of the trace back will typically be some kind of Error (TypeError in the above example).

There are many exceptions built into the python language (full list), the most common ones that you’ll experience are:

| Exception | Cause | Example |

|---|---|---|

| AssertionError | Raised when an assert statement fails. | assert value > 0 when value==0 |

| AttributeError | Raised when attribute assignment or reference fails. | a.b when object a has no attribute b |

| FileNotFoundError | Raised when a file/directory is expected to exist, but doesn’t. | open('test.txt','r') |

| ImportError | Raised when the imported module is not found. | import numpy when numpy not installed |

| IndexError | Raised when the index of a sequence is out of range. | a[5] when a has 5 or fewer elements |

| KeyError | Raised when a key is not found in a dictionary. | a{"days"} instead of a{'Days'} |

| KeyboardInterrupt | Raised when the user hits the interrupt key (Ctrl+C). | |

| MemoryError | Raised when an operation runs out of memory. | np.ones( (1_000_000, 1_000_000) ) |

| NameError | Raised when a variable is not found in local or global scope. | a=b+1 when b is not defined |

| OSError | Raised when system operation causes system related error. | |

| OverflowError | Raised when the result of an arithmetic operation is too large to be represented. | int(1e500) |

| RuntimeError | Raised when an error does not fall under any other category. | |

| SyntaxError | Raised by parser when syntax error is encountered. | a + = 1 |

| TypeError | Raised when a function or operation is applied to an object of incorrect type. ** | 1 + 'two' |

| ValueError | Raised when a function gets an argument of correct type but improper value. ** | math.asin(-2) |

| ZeroDivisionError | Raised when the second operand of division or modulo operation is zero. | 1/0 |

** Note: The TypeError and ValueError are also caused by calling a function with the wrong number of arguments, especially if a function has a mix of required and optional arguments.

Python also allows developers to create their own exceptions by extending the Exception class and giving it their own name, so depending on the libraries you are using you may see exceptions not listed above.

Refer to the library documentation to see what they mean and what causes them.

The first thing to do when reading a traceback is look at the kind of exception that is being reported, and the line on which it was generated.

In the above example we have a TypeError and it is complaining about missing 3 required positional arguments.

The second last line shows the code that caused the problem, and the line above that shows the file and line number of where you can find that error.

In this case it’s line 87 in the make_positions function within the file mymodule/sky_sim.py.

The lines above this show how we got to the offending line.

So line 87 was called within the function make_positions which in turn was called from line 119 of <module> which means the global scope of the file.

Long tracebacks can occur when you have many layers of functions calling functions, and sometimes you even get what look like loops in the traceback.

For the example shown, python is telling us that we also need to supply three more arguments: ref_ra, ref_dec, and radius.

This should be a simple fix!

Occasionally, you will find yourself in a situation where the traceback is quite misleading and the line that raised the error isn’t where your bug is being created. A common example is when you are passing variables to a function that wants to work on a given data type, but you’ve given a slightly different data type. Python is built on the principles of leap before you look, and duck typing, meaning that functions tend not to inspect the types of all the passed variables, but instead assume they have the correct, or at least compatible, data types and only complain when something goes wrong. For example this function:

def add_one(num):

"""Add one to an integer"""

return num + 1

was written to expect num of type int.

However, you can pass float, complex, or even numpy.ndarray type objects and this function will still work.

Passing a str or list or tuple will cause and exception to be raised.

If we passed the argument [a] to the above function we would cause an exception and the traceback would point to the return statement of this function as the source of the exception.

However, this function isn’t the cause of the error.

The cause of the error is elsewhere in our code where we have failed to unpack the list [a] and only pass a to the function.

This is why it is useful to have the full traceback available.

There are of course types of bugs that don’t generate exceptions and these can be hard to trace because we don’t get an execution stack to show us the issue.

An example would be a function dms_to_degrees that turns -00:12:15 into a positive declination instead of a negative one.

There is no exception raised here, because all the code is valid python, but there is an error in the implementation which gives the wrong result.

How can we catch these sorts of errors?

The answer is testing!: we create tests for our functions that raise exceptions when something isn’t doing what we intend it to do.

Getting feedback from your code

There are two key things you need to know when debugging your code:

- What problem has occurred

- Where the problem has occurred

A simple method for determining the above is to have your code be chatty or verbose during it’s execution.

To achieve this you can scatter a some print statements throughout your code so that you know what it’s up to and have a chance at figuring out where an error occurs.

For example you can add some header/footer print statements to your functions:

def get_radec():

...

print("Fetching reference coordinates")

...

print("Done")

return ra, dec

If you find that some error occurs in this function then you might add some extra print statements to tease out the problem:

def get_radec():

"""

Generate the ra/dec coordinates of Andromeda

in decimal degrees.

Returns

-------

ra : float

The RA, in degrees, for Andromeda

dec : float

The DEC, in degrees for Andromeda

"""

print("Fetching reference coordinates")

# from wikipedia

andromeda_ra = '00:42:44.3'

andromeda_dec = '41:16:09'

print(f"Input is: {ra}, {dec}")

degrees, minutes, seconds = andromeda_dec.split(':')

dec = int(degrees)+int(minutes)/60+float(seconds)/3600

print(f"Dec is: {degrees} deg, {minutes} min, {seconds} sec -> {dec} degrees")

hours, minutes, seconds = andromeda_ra.split(':')

ra = 15*(int(hours)+int(minutes)/60+float(seconds)/3600)

print(f"RA is: {hours} hrs, {minutes} min, {seconds} sec -> {ra} hours")

ra = ra/math.cos(dec*math.pi/180)

print(f"RA is {ra} degrees")

return ra, dec

This would help you catch errors where a declination of “-00:12:15” is converted into a positive value. Once you solve the problem, you probably don’t want such a chatty program, so you’d go back and delete most of the print statements. This can cause a lot of churn in your code, and can result in the creation of new bugs (mostly minor ones like unintended ouput, but still bugs). There are a few tools that we can use to replace the above strategy:

- A logging framework that let’s us choose how verbose our program will be,

- A test framework to identify which functions are misbehaving,

- A debugging tool that will allow us to step through the execution of our code and explore variables as we go.

Logging with logging

The logging module provides you with a simple yet powerful way of communicating the state of your program as it’s running.

Setting up a logger is as simple as:

import logging

# configure logging

logging.basicConfig(format="%(name)s:%(levelname)s %(message)s", level=logging.INFO)

log = logging.getLogger("<my module>")

# use the logger

log.debug('This is a debug message')

log.info('This is an info message')

log.warning('This is a warning message')

log.error('This is an error message')

log.critical('This is a critical message')

Your log object will have five levels of logging with intended use as follows:

| Level | Intended use |

|---|---|

| DEBUG | Detailed information, typically of interest only when diagnosing problems. |

| INFO | Confirmation that things are working as expected. |

| WARNING | An indication that something unexpected happened, or indicative of some problem in the near future (e.g. ‘disk space low’). The software is still working as expected. |

| ERROR | Due to a more serious problem, the software has not been able to perform some function. Typically followed by raising an exception. |

| CRITICAL | A serious error, indicating that the program itself may be unable to continue running. Typically followed by sys.exit(1) or similar. |

With the above hierarchy you can tell your logger which level of logs should be shown to the user.

Running log.set_level(logging.WARNING) will cause DEBUG and INFO level messages to be supresed, and WARNING, ERROR, and CRITICAL messages to be printed.

You can change the logging state at any time.

By default the logging module sends all messages to the STDERR stream, but you can redirect this to STDOUT, a file, or a combination of the above, by using a handler.

Something to note about the logging module, is that it will add a compute overhead to your program, even if you set the logging level to be ERROR or CRITICAL.

Essentially, your program is spending time creating a string to send to the logger no matter the logging level.

If you want to only execute some code when the logging level is set to DEBUG you can query the logging state as follows:

if log.isEnabledFor(logging.DEBUG):

... # Do debugging type things that may take a while

Make some logs

Modify your

sky_sim.pycode to make use of the logging module.

- import the logging module and set up a logger called

mylogger- set the default logging level to be

logging.INFO- within each function write a

DEBUGlevel note when you are entering/exiting the function- within the

mainfunction, replace theINFOlevel- Run your code and view the output

- Change the logging level to be

DEBUGand re-run your code- (Extension) Add a command line argument

-vwhich will change the logging level toDEBUG

Debugging with pdb and VSCode

Even after extensive logging and testing, you will eventually end up in the situation where you just want to pause your program at some point and have an explore of the current state to see if things are as expected.

This is where a debugging tool like python debugger (pdb) comes in very handy.

The debugger itself is rather tedious to use (see example) because you need to edit your code to import the debugger and choose where you want stop and look around.

Instead of learning how to do this the hard way we’ll instead use a VSCode plugin which takes the tedium away and gives us a much nicer interface.

(The VSCode debugger isn’t using pdb but rather debugpy which provides all the same functionality.)

Other IDEs have a similar interface which we’ll demonstrate below:

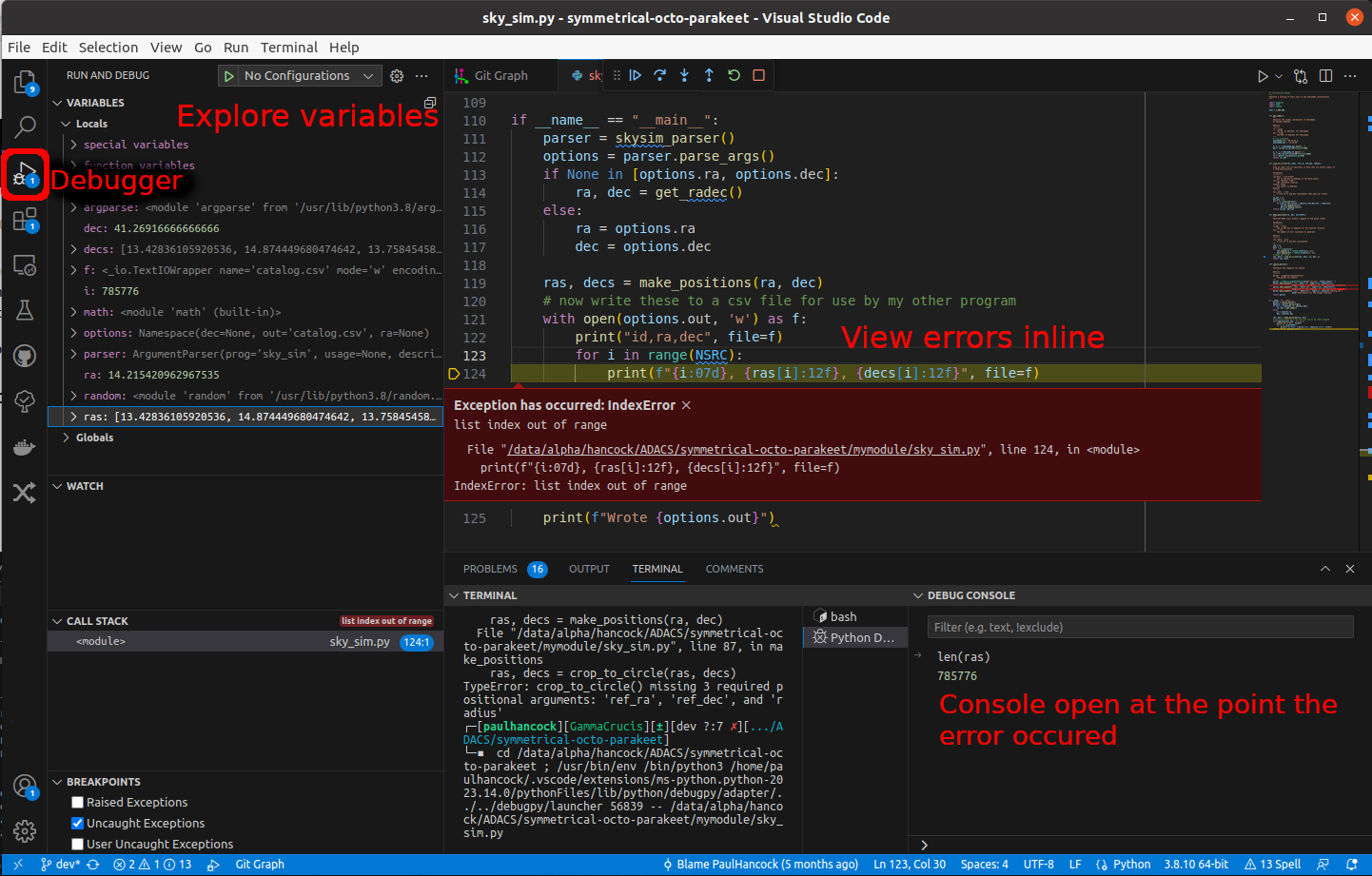

In the above example we have pressed the debugger button, selected a file to run, and then let the errors happen. When an exception is raised the debugger will pause the program and give you the opportunity to explore the state of all the variables using the viewer in the top left, or by writing code int the console on the bottom right.

In the lower left you can see a panel that shows the breakpoints that are going to cause the debugger to stop and enter exploration mode. By default this is set to just “Uncaught Exceptions” but you can add extra break points by clicking to the left of a line of code (it will create a red circle). (Make sure that this is a line of code that python executes and not a blank line or line with only comments.)

When you run your code with a breakpoint enabled the code will stop at the given line.

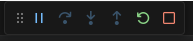

From here you have a set of options shown in the following tool:

The buttons are, in order:

| button | action |

|---|---|

| pause | pause the debugger here (changes to continue when paused) |

| step over | execute the current line of code and pause on the next |

| step into | move into the function, and execute one line of code |

| step out | finish executing all the code in the current function and continue |

| stop | exit (interrupt) the program |

A typical debugging run would look like:

- Identify a line that is known to be working, just before your suspected bug

- Create a break point on this line and run the debugger

- Explore the state of your program at this point in the code, confirm things aren’t broken

- If things are broken goto 1

- Press the step over / step into buttons to execute a single line of code at a time

- Goto 3

- Eventually you find something that is not as expected and you have your bug!

Now you do the following:

- Create a test that fails on this bug

- Modify the code until your test passes

- ?

- Profit

explore the

get_radecfunction

- Within your

sky_sim.pyfile, set a breakpoint within theget_radecfunction on the line where the ra is being assigned.- Run the VSCode debugger on this file.

- When your code is paused by the debugger, use the debug pane to explore what variables exist and their values

- Use the ‘step over’ button to work through the function, noting how the variables change value

Test this function on a negative declination:

- Set a breakpoint as above

- After the declination string is assigned, use the debug panel to change it’s value to be ‘-00:12:15’

- Step through the lines of the program as before and see if you can spot the mistake that is being made

Key Points

Best practice coding will reduce bugs and their severity

Logging is a good way to keep track of what your program is doing

There will always be bugs - don’t feel bad

Use debugging tools