Best Practices In Scientific Computing

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What does best practice mean?

What should I be doing?

What should I try to avoid?

Objectives

Appreciate guidelines for best practice

Work through an exercise demonstrating some of these practices

Be less scared about testing and documentation

Background

Writing software is an integral component of the research activities of many astronomers. Increasingly, such software is written in collaborative efforts involving multiple researchers across multiple institutions. Despite this, training for astronomy students and early career researchers in best practices for collaborative software development is often informal and fails to make use of software industry knowledge. The goal of this course is to fill this training gap.

In this course you will be guided through the development of a software package, beginning at proof of concept, and finishing with a project that is findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable (FAIR), and citable by others. This course is presented in lessons which represent development cycles. Each cycle will be another step along the path of making code that you are proud of and can be recognized for.

At the beginning of this course you will be taken through a typical research driven development phase. In this phase we will create a proof of concept code which we then build on throughout the course. This project is extremely simple in scope as it intended to be a minimum working example that we can use to demonstrate various development techniques. Many of the examples in this course will refer to the example code. If you have an existing software project we recommend that you use that project when doing the various activities as you will encounter more issues, learn more techniques, and the solutions to the activities will be directly usable and beneficial to you.

Best Practices In Scientific Computing

While computer science and software engineering have different goals than scientific computing, many of the best practices in these disciplines are still applicable to scientific computing.

Since the top priority of scientific computing is to have software that produces correct results, we can make our lives easier by adopting practices that make our code or scripts easier to understand (by humans) so that errors can be found and fixed easily. Additionally, since our research work is continuously changing it is very likely that we will revisit our scripts to re-use them (in part or in whole) or expand their use. Here again readability and clarity will be of benefit, but so will version control, and modularization.

Here are some guiding principles that should be followed when planning or writing scripts, regardless of language:

| Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| Clarity over efficiency | Prioritize writing clear code over efficient code. Make use of programming idioms1. Do standard things in standard ways. Write code for humans to understand in the first instance, and only secondarily for computers. |

| Naming is important | Choose meaningful and useful names for variables/functions/classes/scripts. Typically: objects are nouns, functions are verbs, pluralize variables that represent lists or collections. Unhelpful names can be annoying to work with, whilst confusing names can be downright destructive. |

| Don’t repeat yourself | When something works reuse it. Bundle repeated code into functions and call those functions. Bundle functions into modules that can be imported. Write simple (single intent) tools that can be easily incorporated into larger workflows. |

| Don’t repeat others | If something seems routine then there is almost always an existing solution that you can rely on. Look for existing libraries/modules or programs that you can make use of. Don’t reinvent the wheel2 |

| Document | You will forget what you did and why you did it. Write yourself a document that describes the problem you were trying to solve, the approach that you took, and how you solved it. If the solution is a script, then describe how to use the script including the inputs, what options are available, and what the output is. This can be a README.md file, docstrings (in python) or a pdf. The format is less important than the fact that the documentation exists. |

| Test | Only the very lucky get things right the first time. Don’t rely on luck. When you write a script, do something to convince yourself that it works. Manually inspecting results for a known example is form of testing (validation). Where possible automate testing. |

| Version control | When moving towards a solution we often make a wrong turn. Use a version control system to create a ‘checkpoint’ or ‘save point’ that you can easily come back to if things go bad. You don’t need to do pull requests, branching, merging, or upload your files to GitHub for version control to be useful. |

| Avoid premature optimization | Optimization can save time in the term run but always costs time in the short term. Optimize your time by firstly solving the problem, and only engage in optimization after you find out that your code is taking too long or using too many resources3. |

In this lesson we will focus on repetition, version control, testing, documentation, and repetition. To demonstrate the utility of these topics we’ll be working on a common task - simulating a catalogue of stars.

Use case - simulating a sky catalogue

The example project that we will be developing will simulate a catalogue of foreground stars in the direction of the Andromeda galaxy. The initial requirements are as follows:

- Stars should have randomized sky positions around the Andromeda galaxy

- Positions should fall within 1 degree of the central location

- Each star should have a unique ID

- The star ID and position should be saved in a csv file to be analyzed by other programs

This program is intended to be used by the developer and their research group which includes people who are not proficient python programmers. It is intended that the software will grow in capability and complexity only as needed to support a current research project. With this in mind we move to the first stage of our software project – the proof of concept.

With the following requirements, we quickly pulled together some code that works.

- Stars should have randomized sky positions around the Andromeda galaxy

- Positions should fall within 1 degree of the central location

- Each star should have a unique ID

- The star ID and position should be saved in a csv file to be analyzed by other programs

The first iteration of our code is shown below. It was written in a stream-of-conscious mode with a focus on getting a minimum working example that proves that the work can be done.

# Determine Andromeda location in ra/dec degrees

# from wikipedia

ra = '00:42:44.3'

dec = '41:16:09'

# convert to decimal degrees

from math import *

d, m, s = dec.split(':')

dec = int(d)+int(m)/60+float(s)/3600

h, m, s = ra.split(':')

ra = 15*(int(h)+int(m)/60+float(s)/3600)

ra = ra/cos(dec*pi/180)

nsrc = 1_000_000

# make 1000 stars within 1 degree of Andromeda

from random import *

ras = []

decs = []

for i in range(nsrc):

ras.append(ra + uniform(-1,1))

decs.append(dec + uniform(-1,1))

# now write these to a csv file for use by my other program

f = open('catalog.csv','w')

print("id,ra,dec", file=f)

for i in range(nsrc):

print("{0:07d}, {1:12f}, {2:12f}".format(i, ras[i], decs[i]), file=f)

This code runs without any obvious error, and creates a file called catalog.csv.

When we look at the file we see the following first few lines:

id,ra,dec

0000000, 13.699211, 40.583382

0000001, 14.198856, 40.349619

0000002, 13.514020, 41.903174

0000003, 14.050112, 40.359027

0000004, 13.355615, 41.967990

0000005, 13.258444, 41.896025

0000006, 14.815417, 40.406458

0000007, 13.745500, 41.816140

0000008, 14.641606, 40.451957

0000009, 13.374090, 42.162902

0000010, 14.704210, 41.757121

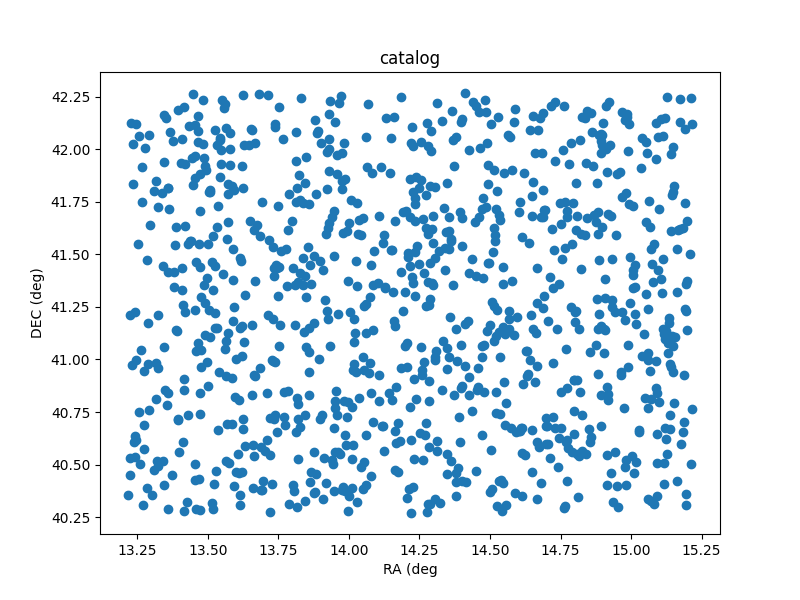

We could use another python script, a jupyter notebook, TOPCAT, or even Excel to plot the data above, and use this to further verify that the data are broadly as expected. The figure below was made with a different python script.

Congratulations, we now have a proof of concept code. It’s not perfect, but it proves to us that our ideas could actually work. Given that this is our first working example of the code, it would be good to set a checkpoint so that if we were to break something in future, we can come back to this version. We should now think about setting up a project, and keeping our work under version control.

Validate the POC

Copy the above code into a new file

sky_sim.py, and verify that it works as intended.If you have problems let us know in the etherpad

By confirming that the code works we have performed some validation testing. We’ll look at how to automate this in a later lesson.

-

See programming idioms ↩

-

Re-inventing the wheel can be a great learning experience, however when you are focusing on getting work done, it’s most often not a good use of your time. ↩

Key Points

Validation is testing

Documentation benefits everyone (especially you)

Version control will save you time and effort