Documentation

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

Why would I document my code?

How do I document my code?

Objectives

Learn how to use python comments and doc-strings

Understand the different types of documentation and audiences

Documentation

To avoid simulating the entire python interpreter in our minds, it is often easier to document the (intended) behavior of our code in a human readable format.

Python offers the builtin function help() to display the documentation for a given function.

Let’s try that now.

Challenge: Get some help

Get some help on the python builtin function

openhelp(open)Solution

Help on built-in function open in module io: open(file, mode='r', buffering=-1, encoding=None, errors=None, newline=None, closefd=True, opener=None) Open file and return a stream. Raise OSError upon failure. file is either a text or byte string giving the name (and the path if the file isn't in the current working directory) of the file to be opened or an integer file descriptor of the file to be wrapped. (If a file descriptor is given, it is closed when the returned I/O object is closed, unless closefd is set to False.) mode is an optional string that specifies the mode in which the file is opened. It defaults to 'r' which means open for reading in text mode. Other common values are 'w' for writing (truncating the file if it already exists), 'x' for creating and writing to a new file, and 'a' for appending (which on some Unix systems, means that all writes append to the end of the file regardless of the current seek position). In text mode, if encoding is not specified the encoding used is platform dependent: locale.getpreferredencoding(False) is called to get the current locale encoding. (For reading and writing raw bytes use binary mode and leave encoding unspecified.) The available modes are: ...

Where does help() get all this information from?

In part, the information provided by help is part of the docstring for the open function.

We can view the docstring by viewing the __doc__ attribute of the function as follows:

Example

print(open.__doc__)Output

Open file and return a stream. Raise OSError upon failure. file is either a text or byte string giving the name (and the path if the file isn't in the current working directory) of the file to be opened or an integer file descriptor of the file to be wrapped. (If a file descriptor is given, it is closed when the returned I/O object is closed, unless closefd is set to False.) mode is an optional string that specifies the mode in which the file is opened. It defaults to 'r' which means open for reading in text mode. Other common values are 'w' for writing (truncating the file if it already exists), 'x' for creating and writing to a new file, and 'a' for appending (which on some Unix systems, means that all writes append to the end of the file regardless of the current seek position). In text mode, if encoding is not specified the encoding used is platform dependent: locale.getpreferredencoding(False) is called to get the current locale encoding. (For reading and writing raw bytes use binary mode and leave encoding unspecified.) The available modes are: ...

Compare the help shown above to the official python documentation here.

Documentation vs commenting

There are two ways in which you can and should describe your code - documentation and commenting. These two ways of describing code have two audiences (which may overlap) - documentation is for the people who will use your code, whilst comments are for people who will develop your code. Both of these audiences include you, the original developer, some 6 months in the future when you have forgotten all the details about what you were doing. Quite simply:

Documentation is a love letter that you write to your future self.

– Damian Conway

Types of documentation

There are lots of different types of documentation and there is no one-size-fits-all approach. The type of documentation you write will depend on the type of code you are writing, and the audience you are writing for.

The following list is a rough order of importance for documentation types and as you software gets more complicated and the audience increases you should consider adding more types of documentation.

Comments

Comments should include design decisions, or explanations of difficult to interpret code chunks. Comments can include known/expected bugs or shortcomings in the code. Things that are not yet implemented, or hacks that deal with bugs in other modules, should also be in comments. Comments are also a good place to reference where you saw a particular idea/approach or even code that you have copied:

def very_smart_function():

# This function is a modified version of <stackoverflow perma link>

...

return

Python comments come in two flavours: a single or part line comment which begins with a #, or a multiline comment which is any string literal.

'''

A comment that covers more than one line

because it is just soooooo long

'''

def my_func(num):

# assume that num is some numeric type, or at the very least

# an object which supports division against an integer

ans = num / 2 # A partial line comment

return ans

The partial-line comment plus multi-line commands can be used to great effect when defining functions, dictionaries, or lists:

dict = {'key1': 0, # note about this item

'key2': 1, # another note

}

def my_func(num,

ax, # a matplotlib axes object

verbose=True, # TODO update to be logger.isEnabledFor(logging.DEBUG)

**kwargs):

...

return

When python is interpreted (or compiled to byte-code), the interpreter will ignore the comments. The comments therefore only exist in the source code. Commenting your code has no effect on the behavior of your code, but it will (hopefully) increase your ability to understand what you did. (Remember: Clarity is important). Because the comments are ignored by the python interpreter only people with access to your source code will read them (developer usually), so this is a bad place to describe how your code should be used. For notes about code usage we instead use documentation.

Docstrings

Python provides a way for us to document the code inline, using docstrings. Docstrings can be attached to functions, classes, or modules, and are defined using a simple syntax as follows:

Example

def my_func(): """ This is the doc-string for the function my_func. I can type anything I like in here. The only constraint is that I start and end with tripe quotes (' or ") I can use multi-line strings like this, or just a single line string if I prefer. """ ... return

Docstrings can be any valid string literal, meaning that they can be encased in either single or double quotes, but they need to be triple quoted. Raw and unicode strings are also fine.

Docstrings can be included anywhere in your code, however unless they immediately follow the beginning of a file (for modules) or the definition of a class or function, they will be ignored by the compiler (treated as a comment).

The docstrings which are defined at the start of a module/class/function will be saved to the __doc__ attribute of that object, and can be accessed by normal python introspection.

Docstring formats

While it is possible to include any information in any format within a docstring it is clearly better to have some consistency in the formatting. (Remember: Clarity is important)

There are, unfortunately, many ‘standard’ formats for python documentation, though they are all similarly human readable so the difference between the formats is mostly about consistency and automated documentation.

Scipy, Numpy, and astropy, all use the numpydoc format which is particularly easy to read. We will be working with the numpydoc format in this workshop.

Let’s have a look at an extensive example from the numpydoc website.

my_package/my_file.py

"""Docstring for the my_file.py module. Modules names should have short, all-lowercase names. The module name may have underscores if this improves readability. Every module should have a docstring at the very top of the file. The module's docstring may extend over multiple lines. If your docstring does extend over multiple lines, the closing three quotation marks must be on a line by itself, preferably preceded by a blank line. """ from __future__ import division, absolute_import, print_function import os # standard library imports first # Do NOT import using *, e.g. from numpy import * # # Import the module using # # import numpy # # instead or import individual functions as needed, e.g # # from numpy import array, zeros # # If you prefer the use of abbreviated module names, we suggest the # convention used by NumPy itself:: import numpy as np import matplotlib as mpl import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # These abbreviated names are not to be used in docstrings; users must # be able to paste and execute docstrings after importing only the # numpy module itself, unabbreviated. def my_function(): print("Hello World!") def documentation_example(var1, var2, *args, long_var_name='hi', **kwargs): r"""Summarize the function in one line. Several sentences providing an extended description. Refer to variables using back-ticks, e.g. `var`. Parameters ---------- var1 : array_like Array_like means all those objects -- lists, nested lists, etc. -- that can be converted to an array. We can also refer to variables like `var1`. var2 : int The type above can either refer to an actual Python type (e.g. ``int``), or describe the type of the variable in more detail, e.g. ``(N,) ndarray`` or ``array_like``. *args : iterable Other arguments. long_var_name : {'hi', 'ho'}, optional Choices in brackets, default first when optional. **kwargs : dict Keyword arguments. Returns ------- type Explanation of anonymous return value of type ``type``. describe : type Explanation of return value named `describe`. out : type Explanation of `out`. type_without_description Other Parameters ---------------- only_seldom_used_keywords : type Explanation. common_parameters_listed_above : type Explanation. Raises ------ BadException Because you shouldn't have done that. See Also -------- numpy.array : Relationship (optional). numpy.ndarray : Relationship (optional), which could be fairly long, in which case the line wraps here. numpy.dot, numpy.linalg.norm, numpy.eye Notes ----- Notes about the implementation algorithm (if needed). This can have multiple paragraphs. You may include some math: .. math:: X(e^{j\omega } ) = x(n)e^{ - j\omega n} And even use a Greek symbol like :math:`\omega` inline. References ---------- Cite the relevant literature, e.g. [1]_. You may also cite these references in the notes section above. .. [1] O. McNoleg, "The integration of GIS, remote sensing, expert systems and adaptive co-kriging for environmental habitat modelling of the Highland Haggis using object-oriented, fuzzy-logic and neural-network techniques," Computers & Geosciences, vol. 22, pp. 585-588, 1996. Examples -------- These are written in doctest format, and should illustrate how to use the function. >>> a = [1, 2, 3] >>> print([x + 3 for x in a]) [4, 5, 6] >>> print("a\nb") a b """ # After closing class docstring, there should be one blank line to # separate following codes (according to PEP257). # But for function, method and module, there should be no blank lines # after closing the docstring. pass

The example above is intentionally extensive, but you should be able to see what is going on. This docstring format allows us to created automated documentation which we will go over later but here is a sneak peak if you would like to see how it is rendered. There are a few parts to the documentation format, some of which are considered essential, good practice, or optional.

Essential documentation

The main goal of documentation is to describe the desired behavior or intended use of the code. As such every docstring should contain at least a one line statement that shows the intent of the code.

Document

input_dataandmolleweide_plotv1For our

input_dataandmolleweide_plotfunctions that we created earlier, add a few lines of documentation to describe the intent of the function.

git commityour changes when you are happy with them(partial) Solution

def input_data(csv_path): """Reads the CSV file and returns a DataFrame with the RA and Dec converted to degrees. """ # Read the CSV file into a DataFrame df = pd.read_csv(csv_path) # Add new columns to df df['RA (deg)'] = 0 df['Dec (deg)'] = 0 # Loop over dataframe and convert RA and Dec to degrees for index, row in df.iterrows(): ra_hms = row['RA (HMS)'] dec_hms = row['Dec (DMS)'] # Create a SkyCoord object and specify the units c = SkyCoord(ra=ra_hms, dec=dec_hms, unit=(u.hourangle, u.deg)) # Access the converted RA and Dec in degrees ra_deg = c.ra.deg dec_deg = c.dec.deg # Update the DataFrame with the converted values df.at[index, 'RA (deg)'] = ra_deg df.at[index, 'Dec (deg)'] = dec_deg return dfdef molleweide_plot(df): """Plots the sources in a Molleweide projection and saves as a png called pulsar_plot.png. """ # Plot the pulsars fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4)) # Molleweide projection gives us a nice view of the whole sky ax = plt.axes(projection='mollweide') plt.grid(True, color='gray', lw=0.5, linestyle='dotted') ax.set_xticklabels(['22h', '20h', '18h', '16h', '14h','12h','10h', '8h', '6h', '4h', '2h']) # Convert RA and Dec to radians and plot ax.scatter(radians(-df['RA (deg)'] + 180), radians(df['Dec (deg)']), s=0.2) plt.savefig("pulsar_plot.png", dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

Good practice documentation

It is good practice to describe the expected input and output (or behavior) of your functions.

In the numpydoc format we put these into two sections:

- Parameters: for the input

- Returns: for the output

There is no “Modifies” section for the documentation (though you could add one if you like). If the function modifies an input but does not return the modified version as an output then this should be included as part of the long form description.

Document

input_dataandmolleweide_plotv2Extend our documentation for

input_dataandmolleweide_plotso that it includes a Parameters and Returns sections.

git commityour changes when you are happy with themSolution

def input_data(csv_path): """Reads the CSV file and returns a DataFrame with the RA and Dec converted to degrees. Parameters ---------- csv_path : str Path to the CSV file containing the source data. Returns ------- df : pandas.DataFrame Pandas DataFrame containing the source data with RA and Dec in degrees. """ # Read the CSV file into a DataFrame df = pd.read_csv(csv_path) # Add new columns to df df['RA (deg)'] = 0 df['Dec (deg)'] = 0 # Loop over dataframe and convert RA and Dec to degrees for index, row in df.iterrows(): ra_hms = row['RA (HMS)'] dec_hms = row['Dec (DMS)'] # Create a SkyCoord object and specify the units c = SkyCoord(ra=ra_hms, dec=dec_hms, unit=(u.hourangle, u.deg)) # Access the converted RA and Dec in degrees ra_deg = c.ra.deg dec_deg = c.dec.deg # Update the DataFrame with the converted values df.at[index, 'RA (deg)'] = ra_deg df.at[index, 'Dec (deg)'] = dec_deg return dfdef molleweide_plot(df): """Plots the source in a Molleweide projection and saves as a png called pulsar_plot.png. Parameters`` ---------- df : pandas.DataFrame Pandas DataFrame containing the pulsar data with RA and Dec in degrees. """ # Plot the pulsars fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4)) # Molleweide projection gives us a nice view of the whole sky ax = plt.axes(projection='mollweide') plt.grid(True, color='gray', lw=0.5, linestyle='dotted') ax.set_xticklabels(['22h', '20h', '18h', '16h', '14h','12h','10h', '8h', '6h', '4h', '2h']) # Convert RA and Dec to radians and plot ax.scatter(radians(-df['RA (deg)'] + 180), radians(df['Dec (deg)']), s=0.2) plt.savefig("pulsar_plot.png", dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

Optional documentation

The type of errors that are raised, and under what conditions, can be documented in the Raises section.

Notes, References, and Examples, are also useful sections but not usually applicable to all functions or classes that you will be writing.

If I have used code snippets from stack-overflow or similar, then I find Notes/References section to be a good place to acknowledge and link to those resources.

The Examples section can be used to show intended use.

There is an automated testing suite called doctest which will scan your docstrings looking for segments starting with >>> and then run those segments in an interactive python interpreter.

A solid test suite will typically contain many tests for a single function, thus trying to embed all the tests into your docstrings just makes for very long docstrings.

It is preferable to keep your testing code in the tests module/directory of your python module (see the episode on testing), and to use the Examples section only for demonstrating functionality to the end user.

That are also tools that can automatically generate documentation from your docstrings such as ChatGPT and GitHub Copilot. These tools are still in their infancy and so the documentation they generate is not always perfect, but is often a good starting point to speed up the process.

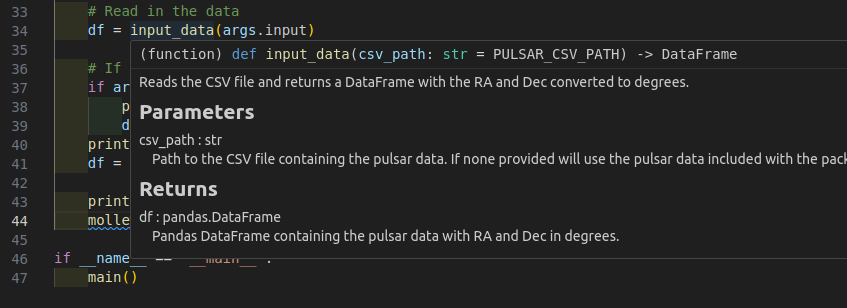

Making use of docstrings

Some IDEs (the good ones) provide syntax highlighting, linting, and inline help as you write code. By providing docstrings for all your functions you can make use of the linting and inline help. Below is an example from VSCode in which the docstring for a function is being shown to me as I code.

You can use the help from the python console like this:

Python 3.10.10 (main, Mar 21 2023, 18:45:11) [GCC 11.2.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> from my_package.data_processing import input_data

>>> help(input_data)

Help on function input_data in module my_package.data_processing:

input_data(csv_path='/home/nick/code/python_project_template/my_package/data/pulsars.csv')

Reads the CSV file and returns a DataFrame with the RA and Dec converted to degrees.

Parameters

----------

csv_path : str

Path to the CSV file containing the pulsar data.

If none provided will use the pulsar data included with the package.

Returns

-------

df : pandas.DataFrame

Pandas DataFrame containing the pulsar data with RA and Dec in degrees.

>>>

Additionally you can compile all the documentation into a website or other document using an automated documentation tool as described in the next section.

README.md

The README.md file is the first thing that people will see when they visit your repository on GitHub. It is therefore important to have a good README.md file that explains what your code does and how to use it. The README.md file should be written in markdown and should contain the following information:

- A brief description of what your code does.

- A list of dependencies (e.g. python packages) that are required to run your code.

- A brief description of how to install your code.

- A brief description of how to run your code.

- A brief description of how to cite your code.

# My Package

This package does some stuff.

## Dependencies

This package requires the following python packages:

- numpy

- pandas

- matplotlib

- argparse

## Installation

To install this package run:

```

pip install .

```

## Usage

To run the code use the following command:

```

filter_and_plot

```

This will create a `pulsar_plot.png` file in the current directory.

## Citation

If you use this code please give credit by citing [Swainston et al 2023](link_to_paper)

CLI help

Consider creating a command line interface (CLI) for your code and providing an option of --help that gives users a quick intro to the use of your code.

For example, the argument parser we created for filter_and_plot in the previous episode outputs useful CLI documentation:

usage: filter_and_plot [-h] [-i INPUT]

Process and filter an input CSV file and create a sky plot of the sources.

options:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-i INPUT, --input INPUT

The path to the input csv file. Default: "pulsars.csv"

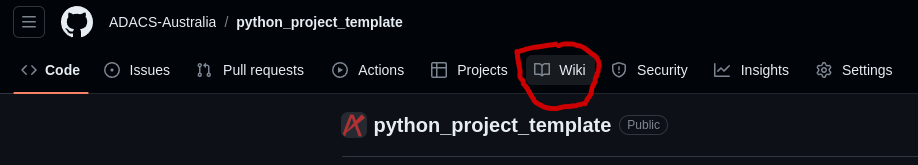

Wiki or Online Documentation

GitHub and GitLab both provide a wiki for each repository.

These can easily be edited in your browser to create some quick documentation.

your github repo wiki is also a repo

- If you have a github repository at https://github.com/[user]/[repo].git, then you can clone the wiki corresponding to that repository from https://github.com/[user]/[repo].wiki.git

- The wiki uses markdown formatting to render the pages.

- You can of course still use the online editor to update the wiki, which is nice, because it has a ‘preview’ button.

Automated Documentation

If your docstrings are formatted in a regular way then you can make use of an automated documentation tool. There are many such tools available with a range of sophistication.

One that is a bit difficult to use but has wonderful auto-documentation packages is sphinx. It can write latex (and thus pdf), ePub, man pages, or plain text. When set up correctly, you can create a GitHub Action to automatically generated documentation and display it on the GitHub Pages for your repository.

Setting up sphinx documentation

First install sphinx using

pip install sphinx

Then you can make sphinx create a documentation template using

sphinx-quickstart docs

Which will create the following files: conf.py, index.rst, make.bat and Makefile in the docs directory.

I recommend changing extensions and html_theme in docs/conf.py to

extensions = [

'sphinx.ext.autodoc',

'sphinx.ext.doctest',

'sphinx.ext.mathjax',

'sphinx.ext.viewcode',

'sphinx.ext.githubpages',

'numpydoc',

'myst_parser',

]

# ...

html_theme = 'sphinx_rtd_theme'

Lets create a page in our documentation that will automatically display the beautiful docstrings we have made for our functions.

To do this we will write the following in a file called docs/my_project_modules.rst

my_package modules

==================

data_processing functions

-------------------------

.. automodule:: my_package.data_processing

:members:

plotting functions

------------------

.. automodule:: my_package.plotting

:members:

my_file functions

-----------------

.. automodule:: my_package.my_file

:members:

Each of these titles and commands is for each of the module files we created in the my_package directory.

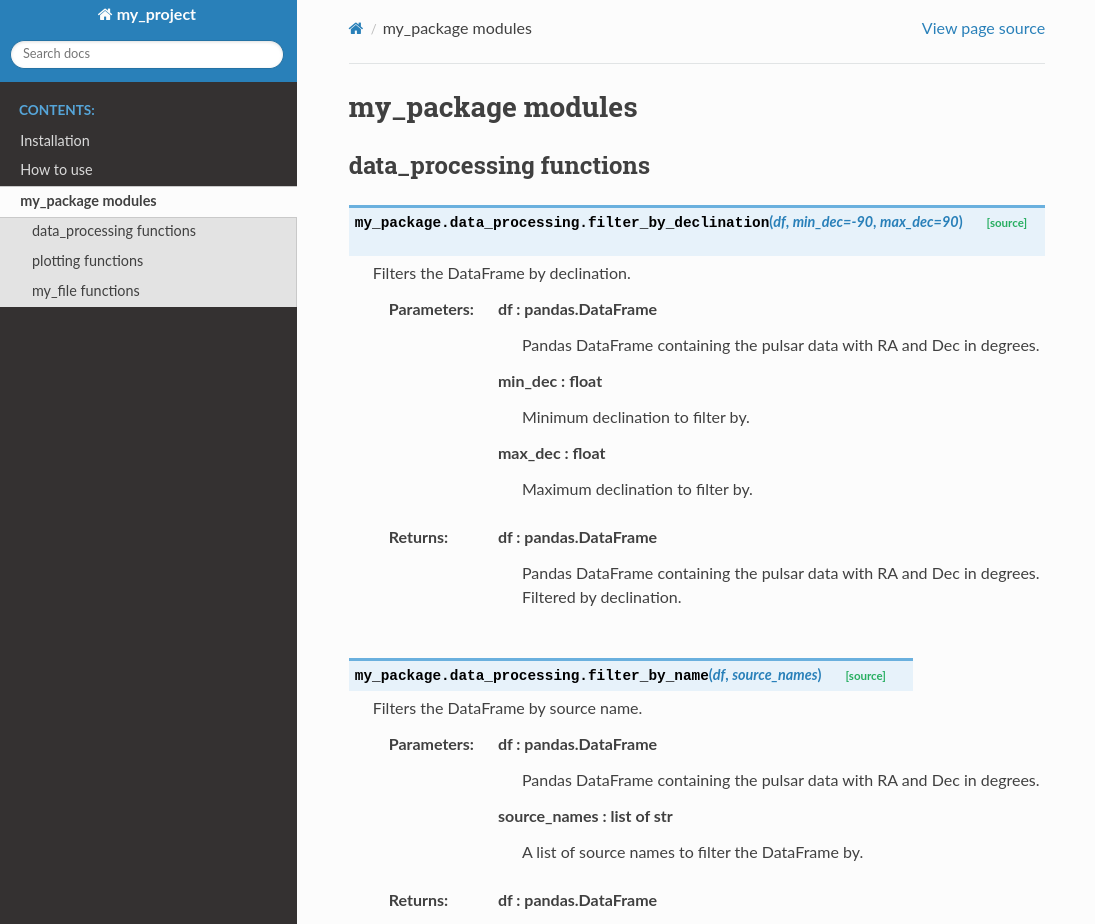

sphinx will find all the functions in those module files and create a human readable webpage with all the information in the docstring.

To add this new page to your contents page, add the following to your docs/index.rst

.. toctree::

:maxdepth: 3

:caption: Contents:

my_project_modules

To test this out, run the following command:

sphinx-build docs html

This will compile the documentation code in the docs directory and output it to a html directory.

Navigate to the html directory with your file manger and open the index.html file with your browser.

You should see a contents page and be able to navigate to the “my_package modules” page which should look something like this

Great! Now every time we update the docstrings, we can update the documentation.

Documentation on GitHub Pages

To make this process even easier, lets set up a GitHub Action to regenerate the documentation every time you push a change to GitHub and update the webpage.

First lets set up a docs/requirements.txt file so that the GitHub Action knows what packages to install.

You can create a file using the command:

pip list --format freeze > docs/requirements.txt

You may have to remove some packages from this file that are not required for the documentation to build. Here is an example that you can use if you run into any issues:

alabaster==0.7.13

Babel==2.12.1

certifi==2023.5.7

charset-normalizer==3.1.0

docutils==0.18.1

exceptiongroup==1.1.1

idna==3.4

imagesize==1.4.1

iniconfig==2.0.0

Jinja2==3.1.2

markdown-it-py==2.2.0

MarkupSafe==2.1.2

mdit-py-plugins==0.3.5

mdurl==0.1.2

myst-parser==1.0.0

numpydoc==1.5.0

packaging==23.1

pip==23.1

pluggy==1.0.0

Pygments==2.15.1

pytest==7.3.1

PyYAML==6.0

requests==2.30.0

setuptools==67.6.1

snowballstemmer==2.2.0

Sphinx==6.2.1

sphinx-rtd-theme==1.2.0

sphinxcontrib-applehelp==1.0.4

sphinxcontrib-devhelp==1.0.2

sphinxcontrib-htmlhelp==2.0.1

sphinxcontrib-jquery==4.1

sphinxcontrib-jsmath==1.0.1

sphinxcontrib-qthelp==1.0.3

sphinxcontrib-serializinghtml==1.1.5

tomli==2.0.1

urllib3==2.0.2

wheel==0.40.0

Next we will create a GitHub Action by creating a file called .github/workflows/docs.yml with the following contents:

name: Sphinx build

on:

push:

branches: [main]

pull_request:

branches: [main]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout repository

uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v4

with:

python-version: 3.10.6 # Replace with your desired Python version

- name: Install dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

pip install -r docs/requirements.txt

pip install .

- name: Build documentation

run: |

cd docs

make html

- name: Deploy to GitHub Pages

uses: peaceiris/actions-gh-pages@v3

with:

personal_token: $

publish_dir: ./docs/_build/html

Lets breifly go through what each of these steps does.

on:

push:

branches: [main]

pull_request:

branches: [main]

This defines when the GitHub Action should run. In this case, it will run every time you push a change to the main branch or make a pull request to the main branch.

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

This defines the job that will be run. In this case, it will run on the latest version of Ubuntu.

- name: Checkout repository

uses: actions/checkout@v2

Will clone and checkout the repository.

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v4

with:

python-version: 3.10.6 # Replace with your desired Python version

Will set up the Python version that will be used to build the documentation.

- name: Install dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

pip install -r docs/requirements.txt

pip install .

Will install the dependencies required to build the documentation and your package.

- name: Build documentation

run: |

cd docs

make html ```

Will build the documentation.

- name: Deploy to GitHub Pages

uses: peaceiris/actions-gh-pages@v3

with:

personal_token: $

publish_dir: ./docs/_build/html

Will deploy the documentation to GitHub Pages.

Git add, commmit, and push this file and you should see a GitHub Action start running.

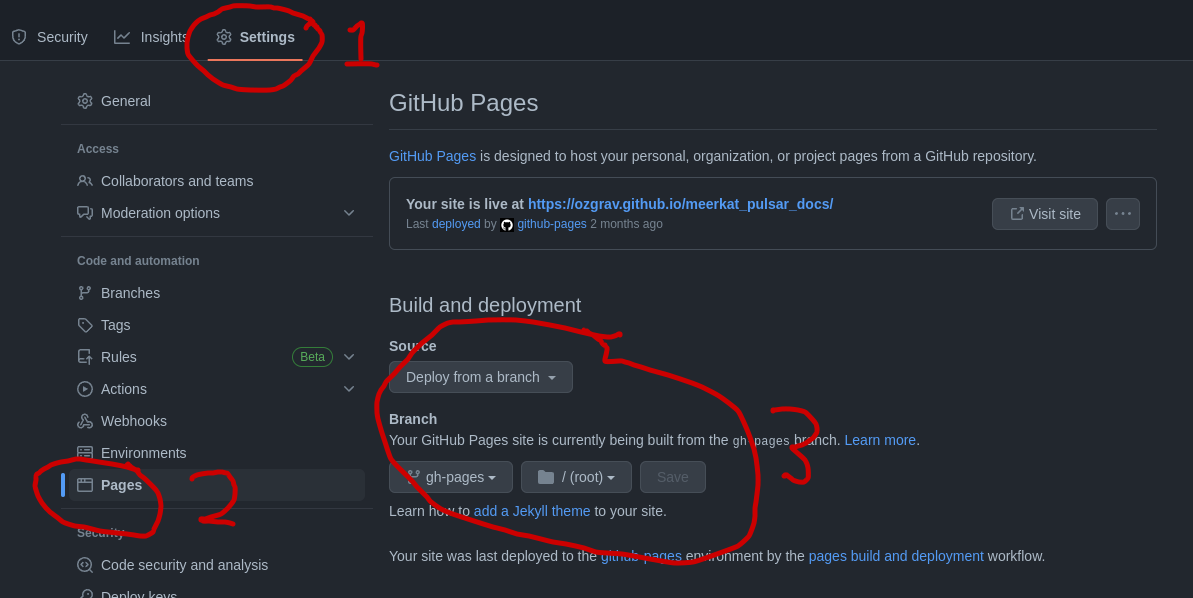

If it completes without errors there should be a new branch called gh-pages and a new webpage at https://<your_username>.github.io/<your_repo_name>/.

If the action fails because you get an error like fatal: Authentication failed you may need to add write permissions to your actions.

Go to your respository’s Setting page, click Actions, General then under Wokflow permissions change it to Read and write permissions.

If you don’t already see the webpage you may have to turn it on in settings by pointing at the root directory on the gh-pages` branch.

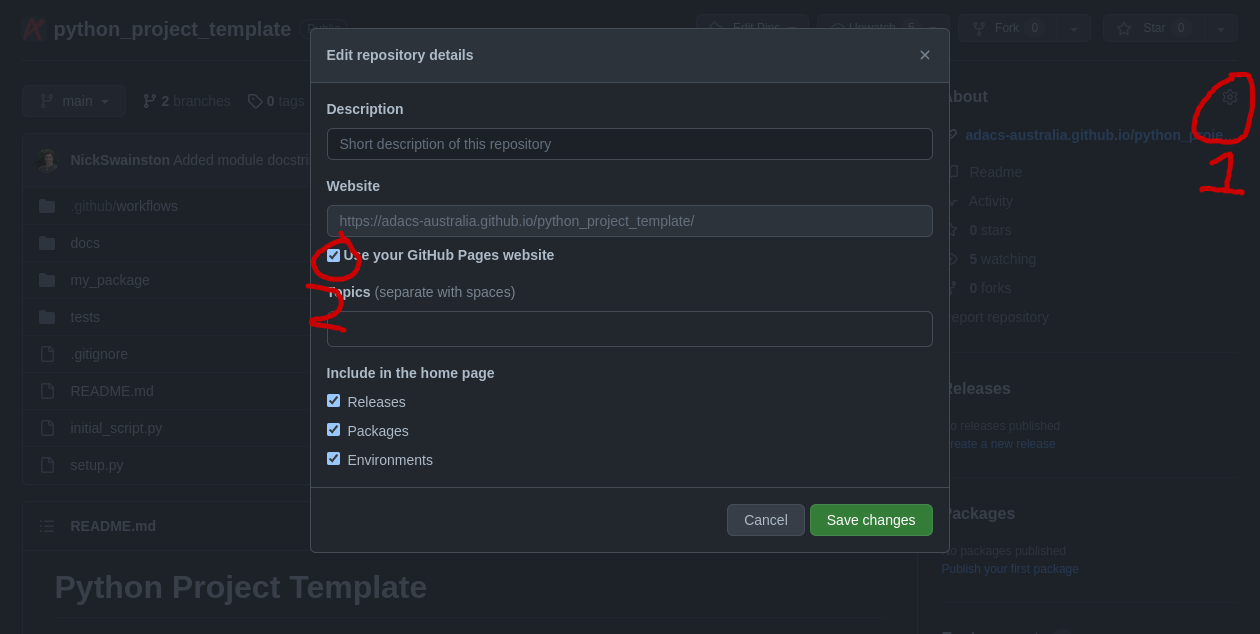

You can then add this link to the GitHub description of your repository so that users can easily find the documentation. You can also add it to the about section on the right by clicking the gear and ticking the box to use your GitHub Pages website.

You documentation is now easy to find and can easily and automatically be updated.

Some futher things you may want to include in your documentation are:

- a guide for downloading/compiling/installing your software

- a ‘quick-start’ guide or set of examples for new users

- a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) section to address common problems

- tutorials to demonstrate some of the key features of your software (Jupyter notebooks are great here)

If you would like some examples of how astronomy software is documentated you can check out:

- AstroPy documentation (an extreme example)

- Aegean wiki (a great example of how to use the GitHub wiki)

- pulsar_spectra (a shameless plug of Nick Swainston’s software)

Key Points

Undocumented code has a steep learning curve, and many people will quit before they begin

If people ask questions about your code, write the answer in the wiki and link them to it

Write a love letter to your future self

Documentation helps with expectation management