More about git workflows

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

I heard branches are a thing, what are they?

How can I connect to multiple repositories?

Objectives

Learn about branching

Review a common workflow with branches

Branching

We mentioned the term ‘branch’ a few times in the previous lessons, but didn’t describe what branches are.

In git terminology a branch is one of the (possibly many) end points on a path that is describe by the commits of your repository.

Until now our repository has been a linear chain of commits, where each commit builds on the previous one like this:

However, at any point in our history, we can have two commits, that are both related to the same parent, essentially making a fork or “branch” in our chain of commits.

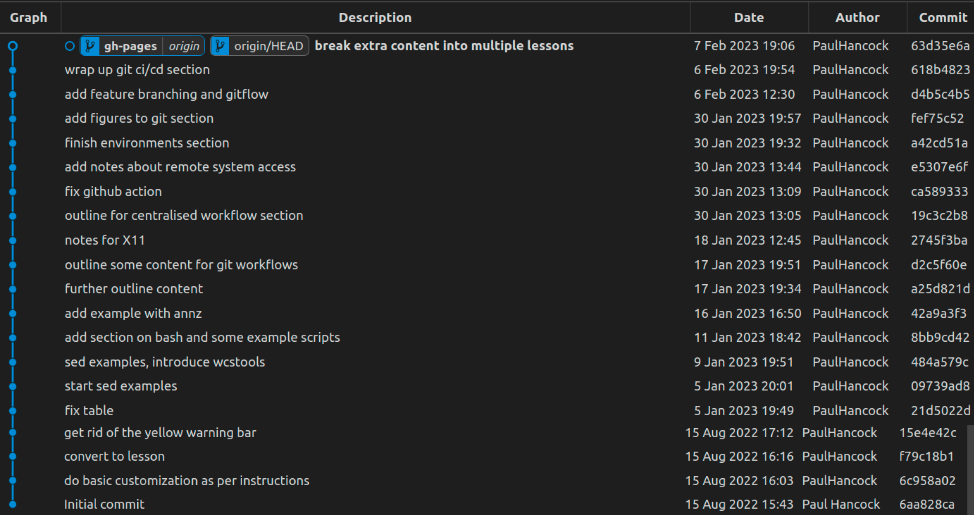

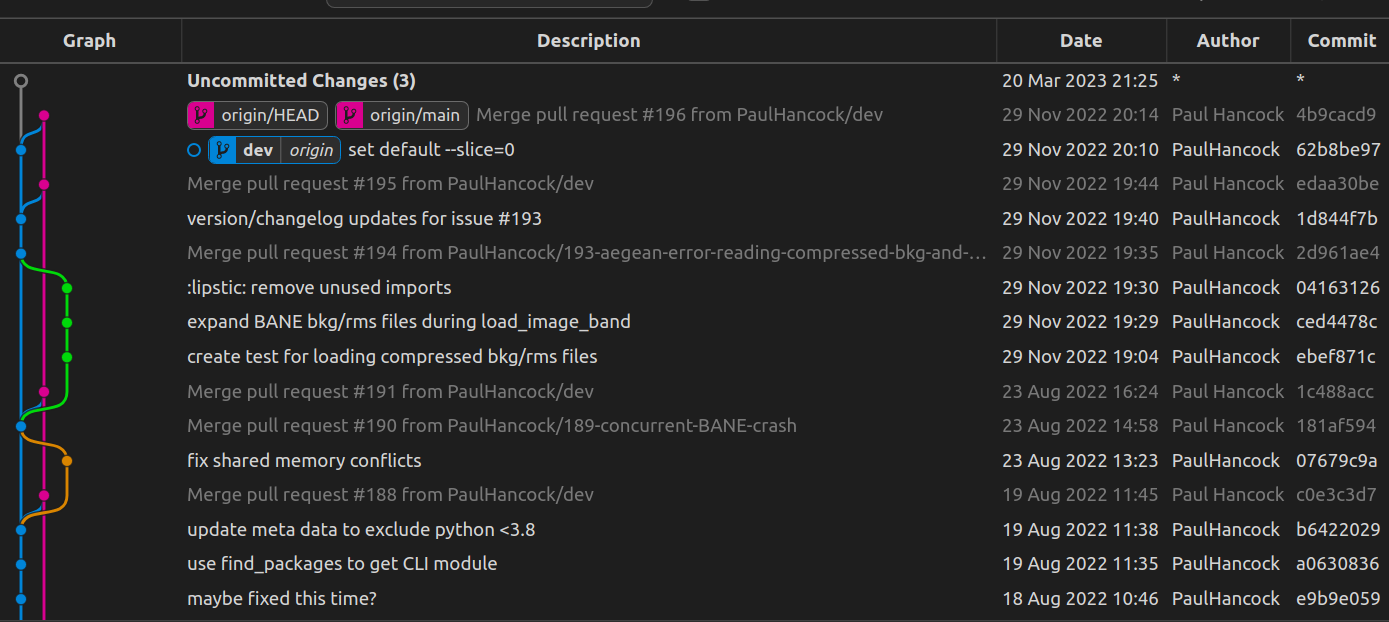

For example, here is a visualization of a project with a main branch (blue), a persistent development branch (pink), as well as a few other short-lived branches (orange/green).

Having multiple branches, and being able to swap between them, means that you can effectively have multiple version of your code in development at once. This might sound scary but you can for example have a main branch that is “always working”, and a development branch that “should work”, and feature branches that are “not working yet”. The thing that makes branches so useful is that you can merge branches onto each other. So when your feature works, you can copy all the commit onto the development branch at once, and then do some testing. This is called merging, and it’s really powerful, but has a risk of causing conflicts.

Git workflows

There are many different workflows that people have described, and this site gives a nice over view of them.:

- centralised

- feature branch

- gitflow

- forking

We’ll just focus on the branching workflow because it’s most relevant to what we are doing.

Feature branching workflow

Similar to the centralized workflow except that when changes are going to be made to the repo a developer will create a branch to work on those changes.

As a feature is being developed changes will often break the functionality of the software so keeping all these changes in a branch separate from main will mean that there is always a ‘known working’ version of the code that people can use.

You could consider the local copies of a repo in the centralized workflow to have a similar purpose to the branches in the feature branching workflow.

However, a key difference is that by having the branches stored in the repository, you can have multiple people seeing and working on these branches.

Another difference is that you can make a different branch for each feature, and have multiple features being developed at the same time.

Consider the case where you are working on a new feature for your code.

You pull the main branch from the centralized workflow and start developing that feature.

As you are part way through you find a bug that needs to be fixed in the code.

You now either have to make that bug fix part of the feature development, meaning that you cant push it back to the main repository until your development is complete, or you have to discard your development in order to fix the bug, before retuning.

Now consider how this would work if you used a feature branching workflow.

You make a new branch from main for feature-1 and start working on it.

You notice a bug in the main code so you create a new branch from main called bugfix-1.

You fix the bug in bugfix-1 and then merge it back to main and then also to feature-1 (possibly using a merge rebase main).

You can now return to developing on feature-1 without having to backtrack.

Another advantage to the feature branching workflow is that by having the branches exist in the central repo, you can have multiple people working on (testing/reviewing) them at the same time. The feature branching workflow includes a new operation that isn’t used in the centralized workflow: a pull (or merge) request. A pull request (or PR) is initiated on the central repository (eg, GitHub), and is a request to pull changes from one branch into another. The idea is that developer A will make a bunch of changes in their feature branch, and then when they are happy with the changes, they will create a PR to merge these into another branch (usually main). Good practice is to then have a different developer act as a reviewer for these changes. Developer B will look at what the feature branch is trying to address, what has changed, and check that tests are still passing, new tests have been created, and documentation has been created/updated. Once the reviewer is happy they approve the PR and the feature branch is merged. For solo developers the PR is not always required, but is still sometimes used as it can cause automated testing to be run. Even in small teams, it can be very beneficial to require all changes to the main branch to be done via pull requests from a feature branch, with some code review and discussion before the PR is accepted. Again, Atlassian have a more detailed description of the feature branching workflow.

Key Points

Branches provide a new place to experiment / develop without braking your main branch